|

CURRENT

ISSUE

SUBSCRIBE

ABOUT

CALIFORNIA WILD

CONTACT

US

ADVERTISING

SEARCH

BACK

ISSUES

CONTRIBUTORS'

GUIDELINES

THIS

WEEK IN

CALIFORNIA WILD

|

feature

Luis Felipe Baptista:

Maestro of the Avian Symphony

Peter Marler

Any Renaissance man would have good reason to be envious

of Luis Felipe Baptista. The amazing breadth of his knowledge, and the

range of his cultural, linguistic, and scientific skills may have been

equaled, but he was unique in the way in which his many talents, rather

than flowing in separate streams, all merged in one creative torrent.

While browsing again through some of his writings,

I came across a 1998 article he wrote for Revista Macau, a forum

for historical records and reminiscences about life and culture in the

former Portuguese colony. Baptista spent the first 20 years of his life

there and in nearby Hong Kong.

In this archival spirit, Baptista wanted to record

his reflections on the dialect of Portuguese spoken there, and to present

a sampling of his experiences as a precocious observer of Asia’s natural

history. The cultural focus of the article shows in its euphonious title,

“Chivit, Bico-chumbo, and other Pastro-Pastro Macaista” (“The white eye,

spice finch, and other birds of Macao”). In it, Baptista recounts his

observations on a dozen birds he was especially familiar with as a schoolboy.

He describes their habits and voices, and records their names in the Macaista

dialect of Portuguese (just one of the five languages in which he was

fluent, often eloquent, and some would say even loquacious).

Baptista seamlessly interweaves these ornithological

recollections with a brief professional autobiography seasoned with reflections

on the ancient Chinese art of aviculture. Again and again he returns to

the music of birds, a lifelong fascination he traces back to a pair of

budgies and a strawberry finch that his brother gave him as a Christmas

gift when he was eight. He learned to imitate the birds by fluttering

his lips and blowing through his teeth, doing well enough to persuade

a pet canary to copy him.

With its delicate spectacles and endearing song, the

chivit was a favorite of serious bird enthusiasts in Macao. These pampered

pets were kept in a handmade Ching dynasty cage, with porcelain feeding

cups and a tiny vase supplied with fresh flowers each day. As a treat,

especially privileged birds were given a peeled water chestnut spiked

on a Mai Tai Chaap, a tiny steel fork clipped outside the cage. The fork

was mounted on an ivory base carved in the shape of a cicada—the symbol

of longevity—or maybe a crab, or a butterfly.

Baptista recalls the ease with which a chivit could

be taught the song of another favored pet bird, the green singing finch

(Serinus mozambicus). While still a schoolboy, Baptista realized

that birds learned their songs by imitation. The theme was destined to

become a major focus of his professional life as an expert on animal behavior

and world authority on bird song. The experience of raising birds sensitized

his ear to the nuances of their songs and taught him many of the avicultural

skills that served him so well later in life as a serious student of bird

behavior.

Chinese school friends initiated him into other ornithological

mysteries, such as the pastor-tira-sorte, or fortune-telling bird (Padda

oryzivora), which can foretell the future. For a fee, the bird’s keeper

opens the door of its tiny cage. The bird presumably subjects the customer

to close scrutiny, hops to a small box full of numbered sticks, and pulls

one out. The fortuneteller lets the bird take a grain of unhusked rice

as its reward before it returns to the cage. The fortuneteller then matches

the number on the stick with a numbered index card and reads the customer

his or her fortune.

Another favorite songster of old Macao, garbed in the

black hood and white cassock of a Dominican friar, was the Dominico, or

magpie robin (Copsychus saularis). Besides enjoying their songs,

the Macaista also staged fights for them and bet on the outcome in a teahouse

that Baptista frequented as a boy. Baptista describes how they are left

to fight until one retreats and crouches motionless in submission while

the other loudly proclaims victory. Baptista’s anecdotes leave us in no

doubt that a childhood immersed in Chinese culture helped to endow the

future ornithologist with a deep love of birds.

In 1961, at the age of 20, Baptista emigrated to California

to attend university; the state remained his home for the rest of his

life. He took degrees at the University of San Francisco and the University

of California at Berkeley, where he acquired what was to be a lifelong

fascination with the song of the white-crowned sparrow, Zenotrichia

leucophrys. Audible everywhere on the Berkeley campus, this bird would

become the subject of more than half of the 120 or so scientific papers

Baptista would publish. Common in Bay Area parks and gardens, the white-crown

was already known to be the supreme example of learned local dialects

in North American bird songs, but no one had made more than a casual effort

to describe exactly how their songs varied from place to place.

In an amazing tour de force, Baptista mapped these

songs in exquisite detail from California to British Columbia. Armed with

a tape recorder, headphones, and his slightly intimidating, parabola-mounted

microphone, he toured tirelessly up and down the West Coast in an old

Mercedes, constantly alert for new song patterns, and infuriating other

drivers by screeching to a halt at the slightest avian sound, blissfully

unaware of the traffic jams he created.

He showed that boundaries between dialects are sometimes

sharp, but often fuzzy, and that birds may be bilingual at the interface.

Using his acutely sensitive ear and remarkable memory, he was able to

infer where birds singing during autumn migration had originated, and

that they uttered songs which locals then later adopted. This became the

classical work on bird song dialects.

Baptista traveled the world to study song and call

dialects of birds. As a fellow of the elite Max Planck Institute for Behavioral

Physiology in Bavaria for a couple of years, Baptista turned his attention

to the chaffinch (Fringilla coelebs). The outcome was probably

the most thorough study ever of geographical variation in a bird call,

as opposed to song. Baptista toured southwest Germany recording and analyzing

nearly 3,500 of the male chaffinch’s “rain calls,” so-called because this

low-level alarm call sometimes heralds an approaching storm. He showed

how the variants are distributed as local dialects, in much the same way

as in the male song. He went on to study the vocal behavior of birds in

many other parts of the world, including the Caribbean, Costa Rica, and

New Guinea.

The California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco

was Baptista’s home base for the last 20 years of his life. He grew to

know practically every resident white-crowned sparrow in Golden Gate Park

personally, and was full of anecdotes about them. A close colleague once

described him as the Henry Higgins of the bird world. “Luis could stand

in the park, hear a call, and declare that ‘the white-crown had a Canadian

father and a California mother. It has half an Alberta accent and half

a Monterey accent. The parents probably met at the Tioga Pass near Yosemite.’”

He did some remarkable experiments on the responses of white-crowned sparrows

to different song dialects.

|

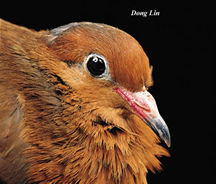

| Luis

Baptista's efforts were crucial to the keeping alive the plan to restore

the Socorro dove (Zenaida graysoni) to its native island off the coast

of Mexico. |

Baptista demonstrated that, although male white-crowns

learn best when young, the timing of song learning is to some extent malleable,

especially if older males are exposed to strong social stimulation. Building

on his youthful experiences with caged birds, he was the first to find

examples of wild birds not known to be habitual mimics that occasionally

learned the songs of other species.

This important finding showed that birds’ preferences

for learning the songs of their own species is not necessarily a consequence

of a physical inability to sing the songs of others. Instead it reflects

a bird’s ability to recognize its own species’ song before it starts to

sing itself.

Perhaps the most compelling example of his prowess

as an aviculturalist was his demonstration in hand-reared Anna’s hummingbirds

that song is learned. Their tiny, delicate babies are among the most difficult

of birds to raise.

Later in life, Baptista became deeply involved in the

conservation of bird populations, especially the 300 or more species of

doves that live in all parts of the world. He will be especially remembered

for the ongoing effort, using captive-bred birds, to reinstate the Socorro

dove on its native island home off the coast of Mexico, where it was extirpated

some 20 years ago. Baptista became an authority on doves, and coauthored

a major monograph on them for the encyclopedic Handbook of Birds of

the World with colleague Pepper Trail and longtime companion Helen

Horblit. Horblit and Baptista presided over a household that often overflowed

with birds of all kinds, to say nothing of the succulents, cacti, and

cycads on which Baptista was also an expert.

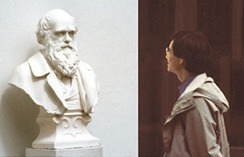

|

| Baptista, on a pilgrimage

to Charles Dawin's home at Down House, England, contemplates a bust

of the great biologist. |

Throughout his life, Baptista’s omnivorous appetite

for knowledge never abated. He appreciated classical music and was participating

in a National Academy of Sciences project on the biology of music and

its relationship to bird song at the time of his death. He was also contemplating

a radically new edition of his comprehensive textbook The Life of Birds,

coauthored originally with the late Joel Welty. This scholar’s goldmine

has already served a generation of ornithologists, including young, aspiring

initiates and their elders in need of intellectual refreshment.

Above all, Luis Baptista was unstintingly generous

with his knowledge. On his office door, he posted a quote from Thomas

Jefferson: “You are here to enrich the lives of others,” a commitment

he honored in full.

Peter Marler

is professor emeritus of biological sciences at the University of California

at Davis.

Reminiscences of Luis

For Luis

Michael McClure

Experience can be said

to have inspired the linnet divinely

but the song is born

from the deep lyric’s grammar

located in flesh inside

of the head.

When the meat and fluff

drops away and the beak is clean

of the touch of the tongue

then the home of the song is gone

though it still is heard

in the forest. To chant,

the troubador must hear

the voice of an elder

master. That makes the

light that brightens

the depths of the skull.

Flutterings transmute

to concertos and garbled

chatter changes

to warblings—the plain

blank field

becomes verdure. Pensive,

the white-turbaned sparrow is listening

but it hears no music

when the towhee calls.

It’s meaningless background

to him. The core of the music is childless

if it has no listener—then

it’s strange as another planet.

|

| Specimen Days with Luis Baptista

Pepper Trail

I had the good fortune to spend many days in the

field with Luis. Of course, for Luis “the field” encompassed any

outdoor locality with a singing white-crowned sparrow, and so included

every patch of greenery in San Francisco. One memorable spring evening,

Luis and I headed into Chinatown for dinner. As we emerged from

the parking garage underneath Portsmouth Square, Luis stopped abruptly.

Holding up a finger, he urged me to concentrate until, finally,

I detected, between the sounds of traffic and the cries of children

drifting over the rooftops, the thin whistle of a white-crown. After

much scanning, we located the bird, perched on a restaurant’s skewed

TV antenna. There was certainly no other white-crown within hearing,

but this wandering bird had found the most appreciative audience

in the world: Luis, grinning from ear to ear, standing at the borderline

between East and West, lost in the beauty of this evening serenade.

Luis astounded many visitors with his encyclopedic

knowledge of the sparrows of Golden Gate Park. Every spring, he

dragged nonplused millionaire donors and bemused world-famous scholars

outside to regale them with tales of avian divorce, duplicity, and

dynastic struggle in the hedges around the Academy. For several

years I also studied the white-crowns of the park. Every afternoon

I would walk into the Birds and Mammals Department and report the

results of the morning’s field work. Luis often knew the identities

of the birds I was studying before I did (it could take days to

get a good look at their color-band combinations), and unfailingly

rattled off their genealogy and the details of their songs. I can’t

count the number of times when he sent me to a distant corner of

the park to search for a particular pair, and there they were.

I traveled to a more exotic locale with Luis only

once, for our study of the St. Lucia black finch. This mysterious

bird had often been mentioned as a possible relative of Darwin’s

finches, but its behavior had never been studied. As we bounced

along the nominal roads that hugged the steep cliffs of this Caribbean

island in our rented jeep, Luis endangered our lives with his hilariously

fractured renditions of reggae songs.

The project was a great success: we found an active

nest and made the first field study of the black finch, confirming

many similarities between the St. Lucia black finch (genus Melanospiza),

Darwin’s finches, and the grassquits (genus Tiaris), as Luis had

predicted.

One night near the end of the trip, we were camped

at a remote cove on the arid east side of the island. This was a

sea turtle nesting beach, and we had been asked by local biologists

to count any turtles that came ashore. We awoke after midnight to

stumble along the beach, the faint moonlight just bright enough

to reveal the weird shapes of the cacti and agaves in the darkness.

Suddenly, we came upon a gigantic form looming up from the sand:

a leatherback turtle laying her eggs. Uncharacteristically speechless,

Luis kneeled down and stroked the strangely soft back of the turtle.

But he could never be close to an animal for long without speaking

to it, and soon Luis was crooning to the mother leatherback in his

quiet, melodic, sing-song way. For over an hour, the only sounds

were the gentle crashing of the surf, the sighs of the laboring

turtle, and Luis’s encouraging voice.

Luis had many special qualities, but perhaps they

came down to this: he was a profoundly encouraging soul. By his

generosity, his intelligence, his curiosity, and his boundless love

of life, he encouraged everyone who knew him. It is hard to imagine

a better legacy. |

| In Search Of Pigeons

Helen Horblit

It was supposed to be a couple of hours’ drive

according to the distance on the map, but we didn’t count on the

roundabouts, and it took more than five hours to drive to the end

of England—Land’s End. We went not to see the smugglers’ caves,

but to see the place where wild rock doves lived, living as ‘pigeons’

were supposed to at the sea’s edge nesting on small ledges above

the treacherous waves. The larks ascending from the bluffs behind

us were a bonus and inspired Luis to whistle Vaughn Williams’s imitation

of the birds.

Afterward, we barreled halfway back across England

to Down House, Darwin’s residence, a point of pilgrimage for island

biologists. Luis wanted to look at Darwin’s stuffed pigeons. He

had been there earlier in the year with his friend Clive Catchpole,

and Luis guiltily related how they had taken turns jumping the velvet

rope in Darwin’s study as the other grown biologist acted as lookout

in case the caretaker came. They sat behind Darwin’s desk in Darwin’s

chair just long enough for evolutionary inspiration to flow.

We arrived after tea, walked the paths where Darwin

walked, and headed for the study. Luis and Clive had been so excited

about their trespass that they never noticed the video security

camera pointed at the desk to catch the pious. We retreated to the

parlor where the glass cases containing the pigeons stood. With

a look perhaps of recognition, the caretaker allowed Luis to hop

the velvet rope for a closer look at the pigeons, still brilliant

after more than 100 years. Luis recognized all the breeds and I

heard him murmur, “So that’s where he was going.” |

|

My Friend, Louie

Bob Drewes

Louie was consumed and driven by his passions.

I remember a function at Pepperwood Ranch, the Academy’s nature

reserve, where the curators were present to interpret the wonders

of the landscape for visitors. Although I was the reptile and amphibian

expert, I quickly learned that if Louie found a frog or lizard or

snake before I did, an immediate lecture on the critter would ensue

from him. And it would be every bit as deep and precise as I would

have delivered. I watched the botanists and the entomologists learn

the same lesson that day. The depth of his knowledge was staggering.

And whoever was standing next to him got the benefit. It was not

really lecturing or teaching that Louie did, it was sharing.

In 1999, Louie traveled to the Bohemian Grove

with me to give a “Museum Talk.” To a first-time visitor, the Grove

can be a very intimidating place. To a first-time speaker, the prospect

of lecturing to a crowd of over 400 men, many of whom are among

the most powerful in the country, can be daunting. Louie was as

eloquent, confident, and powerful as I ever heard him. At the conclusion,

many men came down to the podium and kept him there for questions.

The last and most persistent three included the president of a university,

a world authority on hearing loss, and the director of a well-known

acoustics laboratory.

Later, Louie and I were invited to a place

called Pelican Camp for lunch. Pelicans is a somewhat formal camp

whose membership includes the likes of Walter Alvarez and Richard

Muller, both world-class scientists at Berkeley, a political scientist

or two, and a famous musician. Guests are frequently tapped to speak

extemporaneously. Louie got the nod and proceeded to regale us with

marvelous anecdotes about pelicans. After lunch a group of guest

musicians played the works of an obscure Venezuelan composer named

Astor Piazzolla, who wrote tangos for the accordion. No one else

at our end of the table had ever heard of him, so we were astounded

to learn that Louie not only knew the works of Piazzolla, but his

personal history as well. And, when the group finished, Louie got

up, walked over and embraced one of the older musicians who, it

turned out, had, years ago, played music with his uncle. I remember

being warmed beyond my ability to describe. |

| In the Field

Sandra Gaunt

For those of us who worked with Luis in the field,

his talent as a raconteur took on a whole different color. He was

always animated during the telling of a story, and he often couldn’t

talk, gesticulate, and walk at the same time. This was the case

one particular day in Reserva Biológica Hitoy Cerere in Costa Rica.

Luis, a colleague, and I were fording a rather fast tributary of

the Rio Estrella. It was shallow in only a narrow stretch that forced

us to walk no more than two abreast. Each of us was loaded down

with equipment—binoculars, recorders, microphones, parabolic reflector—and

supplies, and trying not to get anything wet. Luis was in front,

talking a mile a minute when, in the swiftest section, in order

to expand the animation that accompanied his story, he stopped dead.

I am afraid I became quite impatient.

That evening, as we walked back to the camp, I

stopped to examine what I thought was a small frog and was quite

puzzled when Luis piped up, without really being close enough to

see what I was looking at... or so I thought. “That’s a toad bug,”

he said. Sure enough, I found it later in Study of Insects by Borror,

DeLong and Triplehorn—Gelastocoris oculatus—a toad bug! What a day!

|

|

Reminiscences of Luis Baptista Barbara

B. DeWolfe

Luis loved to tell how he transformed his Ph.D.

qualifying oral exam: “When I entered the room I saw six grim-looking

men sitting stiffly upright around the table. Their first question

to me was: ‘Do you know an example of parthenogenesis in vertebrates?’

“‘You mean the Virgin Mary?’ I replied. After that, everyone relaxed.”

A daughter of actor Jimmy Stewart visited Luis

one day and said she would like to work for him. “Just a rich, spoiled

kid,” Luis told me he thought, but he took her outside the Academy

to show her where he was observing white-crowned sparrows. As they

stood talking, a gull flew overhead and deposited its droppings

on Judy’s head. “When the gull shit on her, she never even flinched,”

Luis said. “I knew then she would make a good field assistant.”

(She did.)

Luis was appointed Head of Birds and Mammals at

the California Academy of Sciences in part to effect a more frequent

and favorable rapport with the visiting public. He was superbly

successful at this. Once when Luis was telling a general audience

about his research, his infectious enthusiasm inspired one elderly

lady to ask Luis to give her a wish list of things he needed for

his research. Luis wrote her a letter, telling her in detail his

goals and the equipment he would need. She replied: “I don’t understand

one word of your letter, but please use these stock certificates

to buy whatever you want.” |

|