![]()

Running the T

|

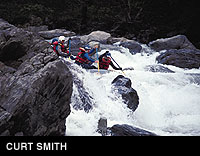

A cold, wet winter carries the promise of a long whitewater

season. That promise was kept by the Tuolumne River last year, so on a brisk September morning I joined eleven

eager folks for the final trip of the season led by O.A.R.S., an Angels Camp-based rafting company. With a dozen

challenging Class IV rapids and strict limits on the number of rafters allowed in its serene canyon, the Tuolumne

sounded like an ideal end-of-summer escape.

This federally protected Wild and Scenic River emerges from its headwaters 13,000 feet up on Mount Lyell and flows along the northern border of Yosemite National Park before passing through Stanislaus National Forest. Rafting or kayaking provides the only access to much of its riparian scenery.

Three dams upstream from our put-in point, including John Muir's nemesis, the O'Shaughnessy, which flooded his beloved Hetch Hetchy, impede the river and control how much will flow each day. The river is running low now, about 1,000 cubic feet per second; it's "bony," so we anticipate a lot of bumping and grinding around and over the exposed rocks. Even at high water, guides call the Tuolumne a "technical" river, with plenty of surprises to test one's whitewater skills.

By way of introduction, Keith Jardine, our guide, asks, "What's the difference between a river guide and a U.S. treasury bond? The bond matures after 30 years and earns money." He takes his guiding seriously, though, and has run this river about 150 times.

As menacing gray clouds threaten to add extra moisture to the trip, we don wetsuits and splash jackets. But by the time we're ready to launch, the sun blesses us with balmy weather, and dragonflies hover low overhead as we shove off into still green water. We soon encounter the first rapid, and appropriately it's called Rock Garden. One of the two boats hauling our gear promptly snags on a rock. Using hand gestures, Jardine directs the oarsman to selectively release air from the pontoons until the raft slowly slides back into the current. Not far downstream the same boat stalls on another rock. This time we employ a less-elegant solution--ramming the raft head-on.

Gazing up at the canyon I'm struck by the contrast between the two walls. The sun-baked, south-facing side is studded with oaks, buckeyes, and ceanothus between expanses of dry grass. On the opposite slope, a dense understory of shrubs beneath pines and lush ferns lines the bank. This area burned ten years ago when 10,000 lightning strikes in one day ignited a firestorm that consumed 130,000 acres. But fires spawn new growth, and this canyon has witnessed countless conflagrations. Downstream we'll see scars of the most recent one, the Rogue Fire that one year ago burned nine miles of ridgetop between the Clavey River and the Tuolumne's North Fork.

That fire catalyzed an amazing display of lupines and poppies in the canyon last spring. And today we're treated to tiny scarlet bursts of native California fuschia sprouting from cracks in gray granite. The rocks sparkle, scoured by winter floods that toppled ash and alder trees and left debris in branches ten feet overhead.

In Sunderland's Chute, a rapid flanked by a gravel bar and a sheer granite wall, a series of big waves pummel our raft, but we emerge with all six paddlers and guide still aboard. Same with the next two challenges, Hackamack Hole and Ram's Head--named for an angular midstream boulder that grows curling horns of water at peak flow.

Three miles downstream we approach Stern, or Tight Squeeze, through which oar boats must enter backwards between the left wall and a huge boulder blocking most of the river. We all raise our paddles overhead to create a bit of breathing room, and our boat barely slips through. Head guide Greg Mally's raft bumps the rock, dislodging two paddlers who are quickly hauled out of the frigid water. I recall a maxim I heard on a previous river trip: there are two kinds of rafters, those who have swum a rapid and those who will.

While watching the river ahead to plot our course, Jardine still manages to keep an eye out for wildlife. He spots a great blue heron perched in a ponderosa pine. Further downstream, he interrupts his commands in mid-rapid: "Forward. Forward. Look up to your left. American kestrel. OK, backpaddle! Backpaddle!"

At Bent Thole Pin, the last rapid for the day, we're warned about a steep drop-off at the bottom. We hit it square, and Jardine gets catapulted from the stern to the middle of the raft, ramming his head into the pontoon. Face-down, he faintly asks another paddler to take over. Fortunately, our intended camp lies just around the bend on the bank of the Clavey River.

A main tributary of the Tuolumne, the Clavey is reduced to a trickle this time of year, much as the Tuolumne would be without the intervention of dams. A scheme to build dams 15 miles upstream on the Clavey--the Sierra's last remaining undammed river--has been silenced for the time being. After hiking upstream, I peel off my wetsuit and sprawl atop a toasty boulder to gaze at the oaks in this gorgeous, golden-brown canyon. I close my eyes to focus solely on the sounds of an unrestrained river.

Within earshot is the Tuolumne's most infamous rafting obstacle, Clavey Falls, and all night I hear the rumble as the river cascades eight feet down the first of three foamy staircase steps that comprise the rapid. Although I've been anxious to put this rapid behind us, now I'm glad that Jardine has a night to rest and recover.

In the morning, as Jardine leads a hike up the Clavey's canyon,

I learn that I've pitched my tent a few yards from a Miwok grinding stone--the smooth, round mortars perhaps exposed

by last winter's floodwaters. Nearby is a mock orange plant, and Jardine describes how the Miwok made arrow shafts

from the second-year shoots.

The canyon contains a geologic jumble of rocks: High Sierra granite, shoved downstream by long-gone glaciers, beside reddish-brown schist, seafloor mud that was crushed and heated deep in the Earth and belched back to the surface. As we boulder-hop toward an inviting swimming hole, water ouzels flit about, dabble in the riffles, and chirp the charming song described by John Muir as "a sparkling foam of melodious notes." The speckled fry of rainbow trout dart in and out from the rocks in deeper pools. In a flash of white and blue, a belted kingfisher zips by, heading upstream. A gravel bar deposited during a massive flood surrounds one side of the swimming hole, and trees scattered like matchsticks attest to the tremendous force with which this river can pound through the canyon.

I scramble over slick rocks and let the Clavey's current carry me down a natural waterslide that submerges me in the pool. We have some time to relax and trade rafting and skiing war stories, but with twelve miles of river left to run today, it's soon time to brave Clavey Falls.

A common merganser placidly passes in front of our raft as we approach the spot where the river vanishes from view. Perched in the bow, I dig my paddle twice into the water and then drop to one knee as we plunge over the falls. The raft bucks and spins at the bottom, but as the second drop-off looms we have recovered our position. Paddling hard, we power through a wave in a hole that could easily flip the raft. Backpaddling, we slip sideways over the third step and head for a still eddy to watch the next raft negotiate the rapid. All paddles rise for a mid-raft high five.

The rapids come more sporadically now, but we have exciting rides through Gray's Grindstone and Rinseaway--a particularly apt name from my front-row seat. In Hell's Kitchen, we careen off rocks like a pinball and come to a halt against a boulder on the left side. "This is where the guided portion of the trip ends," jokes Jardine, who then pries us loose with his paddle while we dutifully bounce on the pontoons. Meanwhile, the raft upstream loses two paddlers, and we spot a pair of red-helmeted heads bobbing in the froth. Jardine leans over and snatches hold of the life jacket of the first swimmer, who's celebrating his 60th birthday on this trip. A lone kayaker intercepts the second swimmer and tows him to our raft.

The last few miles go by languorously, marked by less challenging rapids and no more mid-water rescues. We reach the take-out point, secure the rafts, and board a bus for the precipitous but anticlimactic climb out of the canyon. My quick escape has ended, and I reluctantly embark on what seems a far riskier journey, the three-hour drive home.

|

Where & When |

| Whitewater rafting season on the Tuolumne River starts in April and lasts into the summer or fall. Only two commercial parties, each with a maximum of 20 participants, are permited per day. In Spring, the weather tends to be cooler and the rapids bigger. OARS offers one- to three- day trips down the 18-mile stretch from Meral's Pool to Ward's Ferry. For more information contact OARS at (800)346-6277 or http://www.oars.com. Information about other outfitters who run the Tuolumne and other rivers in the region can be obtained from the River Center Hotline at (800) 552-3625. |

![]()