James Kivetoruk Moses was born in 1900 near Cape Espenberg at the southern entrance to Kotzebue Sound. Orphaned at a very young age, he was adopted and raised by an uncle who made a meager living by hunting and trapping. He and his uncle spent much of the winter trapping, and in the spring they would hunt seal, walrus, and oogruk (bearded seal). This schedule left little time for formal education and Moses attended school only sporadically for about two years. Hunting and trapping provided all the practical knowledge he needed to survive.

When he was about 14 years old, Moses worked at the Magid Store in Deering, and during his spare time he completed a few drawings. In an interview with Yvonne Mozee, published in 1978, Moses recalled that as soon as a drawing was finished, a white woman (probably Mrs. Bessie Chamberlain, the wife of the store owner) sent it away, possibly to Fairbanks. As Moses grew into adulthood, his ambition was to return to trapping and herding reindeer, and so he gave up his art.

|

"Old

Time Eskimo Belle" ca. 1963 Ink and photographic pencil on paper 19.5 x 27.0 cm CAS 0370-1018 |

By the early 1930s, Moses took another trading job in Espenberg, working for John Backland, Jr. whose trade vessel, the C. H. Holmes, had delivered supplies as far north as Barrow since before 1900. Unable to write or keep inventories, Moses was advised to hire a secretary or bookkeeper. At the time, Bessie Ahgupuk (sister of artist George Aden Ahgupuk) was attending the White Mountain Industrial School in Shishmaref. Moses and Bessie Ahgupuk married in 1932, and thereafter, his wife wrote all the supply orders and kept the inventory for the store.

In 1953, Moses was returning by plane from a fishing trip at Bristol Bay. During a storm, the plane crashed into Ear Mountain near Shishmaref and one of Moses' legs was severely injured. While recuperating in the hospital from several operations, he again took up drawing. He knew that he would never be able to hunt and trap again for a living. From then on, his art was his main source of income.

Moses' style of drawing is very different from that of his contemporaries, particularly in its degree of detail. His drawings were, for the most part, based on actual people, places, and events that he personally experienced or saw. In this sense, his works are truly documentary.

Moses worked in various media and used paper or poster board as his canvas. Although he considered oil paints to be the best, he only used them sparingly because they dried too slowly and they were rather costly. Most of his works are done in a combination of pen and ink, watercolor, or oil (photographic) pencil. Through the use of subtle shading and various colored pencils, he was able to capture a high degree of realism and depth in his drawings.

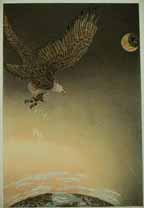

|

Untitled (Man

and Eagle) ca. 1963 Ink and photographic pencil on paper 26.5 x 39.2 cm CAS 0370-1021 |

Moses used several recurring themes in his drawings, including shamans, the advent of white men in northern Alaska, and Eskimo legends. He often did several versions of the same drawing, especially when he was interpreting a story from the oral history. Sometimes he would initially complete a small drawing, and then draw an enlarged version at a later date. For an additional $5, someone buying a drawing could often get a handwritten statement by Bessie Moses explaining the subject. These provide especially useful documentation.

Besides the three drawings by Moses at the California Academy of Sciences, large bodies of his work are in the collections of the Anchorage Museum of History and Art, the University of Alaska Museum in Fairbanks, and the Alaska State Museum in Juneau. The National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City also has a number of his works. He is widely represented in private collections throughout the United States.

After suffering a stroke in 1974, followed by heart and knee surgery a few years later, Moses continued to draw as much as he could, but his output had slowed tremendously. In 1976, his and Bessie's eldest child, James, Jr., disappeared near Nome and was never found. Their other four children had previously died, leaving Moses and his wife all alone. By 1978, he was no longer drawing at all, and he died in 1982.

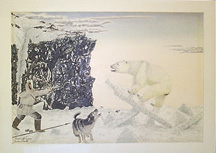

|

Untitled

ca. 1965 Ink and colored pencil on posterboard 26.6 x 39.1 cm CAS 2000-0010-0001 |

![]()

James Kivetoruk Moses Reading List

Archuleta, Margaret and Rennard Strickland

Shared Visions: Native American Painters and Sculptors in the Twentieth Century. New York: The New Press, 1991.

Davidson, Carla

"Arctic Twilight: The Paintings of Kivetoruk Moses." American Heritage, Vol. 26, No. 4, pp. 16-21.

Frederick, Saradell Ard

"Alaskan Eskimo Art Today." The Alaska Journal, Vol. 2, No. 4, 1972, pp. 30-41.

Lee, Molly

"Betwixt and Between: The Art of James Kivetoruk Moses." Eskimo Drawings. Suzi Jones, ed. Anchorage: Anchorage Museum of History and Art, 2003, pp. 103-121.

Melovidov, Mary Jane Anuqsraaq

"James Kivetoruk Moses." Eskimo Drawings. Suzi Jones, ed. Anchorage: Anchorage Museum of History and Art, 2003, pp. 123-125.

Mozee, Yvonne

"A Conversation with Eskimo Artist Kivetoruk Moses." The Alaska Journal, Vol. 8, No. 2, 1978.

Ray, Dorothy Jean

A Legacy of Arctic Art. Seattle: University of Washington Press for the University of Alaska Museum, 1996.

Ruoff, A. LaVonne

Literatures of the American Indian. Broomal: Chelsea House Publishers, 1991.

Woodward, Kesler

Painting in the North: Alaskan Art in the Anchorage Museum of History and Art. Anchorage: Anchorage Museum of History and Art, distributed by the University of Washington Press, 1993.

Yorba, Jonathan

Drawn from the Surroundings: The Elkus Collection of Eskimo Paintings. San Francisco: A. S. Graphics, San Francisco State University, 1990.

![]()