|

||||

Fourth CAS Madagascar Expedition

|

| The CAS Expedition crew from top row (standing) from left to right: Dr. Kipling Will, Roberta Brett, Dr. David Kavanaugh (team leader); second row: Emile Randrianirina, Jean Samuelson Randrianarisoa, Kathryn Kavanaugh, Flor Vargas, Ravu Ranaivosolo, Charlie Raveloson, Nicolas Ranivoson; bottom row: Emily Elsom, Nicole Rasoamanana, Tsil Ravelomanana |

|

In January 2001, the California Academy of Sciences launched its third expedition to Ranomafana National Park, located in southeastern Madagascar. The field team, all entomologists, was led by Curator and Director of Research Dr. David Kavanaugh. Accompanying Dave were two of his graduate students from San Francisco State University (SFSU)--Roberta Brett, who is also a Senior Curatorial Assistant at the Academy, and Emily Elsom, a Graduate Assistant at the Academy. Flor Vargas, an undergraduate student at SFSU and intern in the Education Department at the Academy, field assistant Kathryn Kavanaugh, and Dr. Kipling Will, from the University of Arizona, completed the U.S. part of the team. Once in Madagascar, the Academy researchers were joined by six Malagasy graduate students from the University of Antananarivo, including Ravu Ranaivosolo, Emile Randrianirina, Nicole Rasoamanana, Tsil Ravelomanana, Charlie Raveloson and Nicolas Ranivoson. |

|

The

primary goal of the expedition was to continue the survey of the

terestrial arthropod fauna of the Park that began with the

first expedition in the Spring of 1998. The team's main focus

for this field period was to sample the carabid beetles of the Park.

Dave, Kip, Roberta, and Emily are all engaged in research programs

devoted to the study of this family of beetles. However, significant

collecting effort was directed also at sampling other selected insect

groups (such as Neuroptera, Homoptera, Hymenoptera, and non-carabid

Coleoptera), arachnids (such as spiders, scorpions, daddylonglegs)

and myriapods (centipedes and millipedes).

|

| The entomologists search for carabids along the secondary flood plain of the Namorono River. |

|

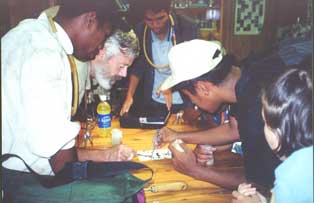

The second major goal of the expedition was to provide a collaborative research and training field experience for the Academy graduate students, Academy undergraduate intern, and our Malagasy student colleagues. For all the Academy students and for several of the Malagasy students, this was their first major, intensive field experience. Training sessions were provided for all the students in a full array of collecting, field preservation, and data recording techniques. Lectures and more informal discussions provided background, context, and rationale for the fieldwork itself. The desired end of all of these activities was to increase personal competence and fuel long-term interest in continuing educational and research pursuits in entomology. |

|

|

|

Hard

unceasing rains, typical of the monsoon season, punctuated the month-long

trip and made collecting difficult at times, but the team was productive

nonetheless. Each day, they ventured out to localities throughout

Ranomafana NP as well as sites beyond the protection of the national

park, literally beating the bushes, turning over rocks, scratching

tree bark, splashing riverbanks and searching rotten logs for insects.

Many insects and arachnids are only active at night and were found

by visually scanning the forest's vegetation lit by the researcher's

headlamps. When torrential rains did not prohibit it, ultraviolet

and mercury vapor light traps were set up to collect insects attracted

to them.

|

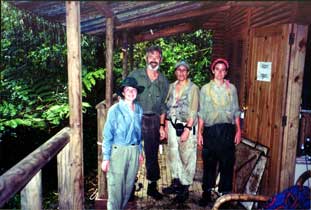

A

bit worse for the wear, the CAS entomologists emerged from the forest

wet, dirty, smelly, and leach ridden, but happy. A

bit worse for the wear, the CAS entomologists emerged from the forest

wet, dirty, smelly, and leach ridden, but happy. |

|

|

|

|

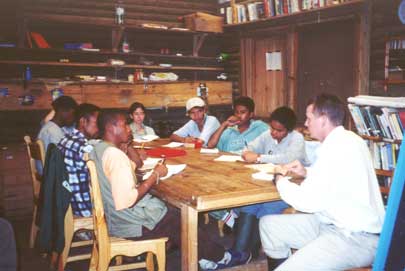

Each morning following breakfast, the team would gather to compare notes and sort through the material collected the day and night before. Through their efforts, over 1700 carabids representing about 75 species were collected, as well as several thousand other insects and arachnids. Included among these were several species of Carabidae not previously recorded from the park. The insects were then carefully packed to ensure their safe arrival back at CAS where they would be pinned, labeled and more thoroughly examined and identified. It is too early to tell, but it is quite likely there were species collected that are new to science! A list of species being compiled for the Park is expanding with each expedition. In particular, a species list and identification guide of the Platynini, a tribe of carabids that is highly diverse (with more than 60 species represented) in the Park, is being developed by Emily as part of her master's thesis. |

|

These specimens provide important information about the Park's biodiversity. Knowledge gained about many of these species may allow them to be as indicators of environmental health in the future. Previous inventories of the carabids in the Park focused on mass collecting methods, such as the use Malaise flight traps and light traps, so little was known about the microhabitat preferences of the species collected. A key to maintaining viable populations of these beetles and other organisms in the Park is to know where they live. Because most of the carabids were hand-collected on this trip, the scientists were able to record the exact conditions under which they were found. Most carabid beetles are predaceous on other invertebrates and are usually found on the ground in temperate regions of the world. However, in tropical rain forests such as at Ranomafana, many species are arboreal. Suggestions for why this is true include avoidance of intense competition with ants on the ground or the danger of being swept away off the forest floor by runoff from heavy rains. |

|

|

The activity of these beetles in January 2001 was relatively low compared to March-April sampling in 1998, and there were few observations of beetles on the ground, on tree trunks and on foliage surfaces at night when they are typically active. This suggests a seasonality to the activity of most adult carabid species, probably centered around the early peak of the rainy season, which is usually late November to early January. Hot and dry conditions prevailed when the team first arrived, but it changed to cooler and wetter weather later. There was a marked increase in both beetle activity and sampling success as wet conditions became sustained. Carabids typically found in trees (arboreal) were found only in masses of leaf and twig debris on or near the ground, not on the tree foliage and trunks as seen in 1998. The scientists believe these masses may serve as refuges for the arboreal carabids during the dry season and may be extremely important to the survival of these species in the Park. Once the wet season is in full swing, these same species move out into the trees from these refuges and search for other insects on which they prey. With this information, the CAS scientists were able to inform Park administrators about the health of its habitats. Park officials and resource managers were eager to learn if there were any negative effects on the Park due to increased tourism in the area. While the team could see no evidence of that, they suggested that the current trail system continue to be maintained and the massive accumulations of dead leaves and twigs that develop periodically at various places throughout the Park be allowed to remain intact. These may serve as important refuges for carabid beetles and other moisture-loving invertebrates during the dry season. |

|

The marked seasonality of the organisms found on this trip suggests the need for a year-round sampling program to properly inventory the terrestrial arthopod fauna of the Park. Future trips to Madagascar are being planned as CAS will continue its commitment to collaborate with the Malagasy government in its efforts to document the biodiversity of its country-diversity that continues under threat of expanded clear-cutting of the little remaining native forest for fuel and agriculture. But the long-term success of our efforts is best assured by the development of expertise within Madagascar that will support continued study and year-round sampling and monitoring of biodiversity. Our commitment to assist with the development of a strong and capable cadre of Malagasy scientists to carry on and expand this effort remains firm as well. |

|

|

|

A

traveler's palm, Ravenea madagascarensis, is a familiar native

tree in Madagascar

|

Updated May 14, 2001